2 cities

6 villages

8 days

18 flights

22 legs

1 jet-lagged individual

Now I'm going to go sleep for a week.

Friday, July 20, 2012

Scammon Bay

Day 6: Scammon Bay, July 17, 2012.

Scammon Bay was my favorite so far. So many locals gathered to talk informally to us, all of whom seemed to be related. It was also the most charming location of any of our villages, nestled in a hillside along the Kun River only a mile from the Bering Sea. Beautiful rock outcroppings mark the boundaries of town and wilderness, home to "little people" who are thought to bring bad luck. Fortunately for us, our luck overall on this trip was excellent, and I hope to return.

Scammon Bay was my favorite so far. So many locals gathered to talk informally to us, all of whom seemed to be related. It was also the most charming location of any of our villages, nestled in a hillside along the Kun River only a mile from the Bering Sea. Beautiful rock outcroppings mark the boundaries of town and wilderness, home to "little people" who are thought to bring bad luck. Fortunately for us, our luck overall on this trip was excellent, and I hope to return.

Hooper Bay

Day 5: Hooper Bay, July 16, 2012.

By now these places are starting to blend together. The buildings we are sent out to survey are cookie-cutter images of each other, making the work ubiquitous from one village to the next. But the villages themselves... they are not the same. Some leave me with a longing to explore further, to get to know the place and the people.

The flight to Hooper Bay was a surprise. Seven people crowded around the door to the runway when the flight was called, which was unusual to say the least. So far our flights into a village had been us + cargo, or perhaps one other person. What could possibly be happening at Hooper Bay to entice 5 others to board? In fact, this flight carried no cargo but that belonging to the passengers.

Our fellow passengers included a couple of folks enlisted for the medical clinic, two guys contracted to install a new fuel tank for the village school, a local, and us. The flights themselves are noisy affairs that don't lend themselves to conversation, but upon landing some of us huddled in the frigid wind waiting for our rides.

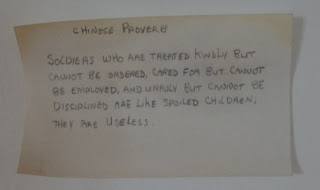

There are people who you want to associate yourselves with in any situation, and those you wish you could politely step away from. "I'm not with them," you want to say to the local community, because of word, deed, or just vibe. There might have been a woman on our flight that made me have these thoughts... And yet... In this job, we swoop in and practically demand that the village community share thoughts, feelings and history with us, without preamble or justification. We are usurpers in our own way, demanding nothing but information from strangers. Are we any better than the typical "rude American," with assumptions that people will want to talk to us, want to share all? Are we any better than those that came before us?

By now these places are starting to blend together. The buildings we are sent out to survey are cookie-cutter images of each other, making the work ubiquitous from one village to the next. But the villages themselves... they are not the same. Some leave me with a longing to explore further, to get to know the place and the people.

The flight to Hooper Bay was a surprise. Seven people crowded around the door to the runway when the flight was called, which was unusual to say the least. So far our flights into a village had been us + cargo, or perhaps one other person. What could possibly be happening at Hooper Bay to entice 5 others to board? In fact, this flight carried no cargo but that belonging to the passengers.

Our fellow passengers included a couple of folks enlisted for the medical clinic, two guys contracted to install a new fuel tank for the village school, a local, and us. The flights themselves are noisy affairs that don't lend themselves to conversation, but upon landing some of us huddled in the frigid wind waiting for our rides.

There are people who you want to associate yourselves with in any situation, and those you wish you could politely step away from. "I'm not with them," you want to say to the local community, because of word, deed, or just vibe. There might have been a woman on our flight that made me have these thoughts... And yet... In this job, we swoop in and practically demand that the village community share thoughts, feelings and history with us, without preamble or justification. We are usurpers in our own way, demanding nothing but information from strangers. Are we any better than the typical "rude American," with assumptions that people will want to talk to us, want to share all? Are we any better than those that came before us?

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

Akiachak

Day 4: Akiachak. July 15, 2012

When we landed in Akiachak, the first thing I noticed were the mosquitoes. Not to put to fine a point on it, but the little bastards were swarming, some the size of grown men, all poised to suck the life right out of us.

This was the first flight where we were literally the only cargo --- being Sunday, there was no mail, and no other passengers were headed our way either. As such, the village agent to his time getting to the landing strip. In all of our village interactions we had made previous contact with the tribal centers. Usually, this meant a local would meet us at the airport and give us a ride into town --- a surprisingly efficient system that had not failed us yet. In Akiachak, because we were arriving on a Sunday, we had no tribal liaison attending us. Instead, we were planning to huff it the 1-2 miles into town. The presence of billions of mosquitoes, not to mention the low-lying shrubbery that was certain to house bears, made that a less than awesome prospect. Thankfully, the Era agent headed out to meet us, giving us a ride into the village and saving us from the potential for being mauled by a bear or worse --- the certain death that lay from a million tiny mosquito bites.

Unfortunately, this is the sum total of my experience in Akiachak. Intermittent rain storms and the aforementioned fact that it was Sunday (and everything was closed) kept us from interacting with anyone from the town or getting a real sense of its vibe. So far, every town has its own unique personality, but with Akiachak I did not experience any of this. It is the curse of this job, really; we blow into town long enough only to get the barest feel of a place, and then, like a puff of smoke or a light breeze, are gone.

When we landed in Akiachak, the first thing I noticed were the mosquitoes. Not to put to fine a point on it, but the little bastards were swarming, some the size of grown men, all poised to suck the life right out of us.

This was the first flight where we were literally the only cargo --- being Sunday, there was no mail, and no other passengers were headed our way either. As such, the village agent to his time getting to the landing strip. In all of our village interactions we had made previous contact with the tribal centers. Usually, this meant a local would meet us at the airport and give us a ride into town --- a surprisingly efficient system that had not failed us yet. In Akiachak, because we were arriving on a Sunday, we had no tribal liaison attending us. Instead, we were planning to huff it the 1-2 miles into town. The presence of billions of mosquitoes, not to mention the low-lying shrubbery that was certain to house bears, made that a less than awesome prospect. Thankfully, the Era agent headed out to meet us, giving us a ride into the village and saving us from the potential for being mauled by a bear or worse --- the certain death that lay from a million tiny mosquito bites.

Unfortunately, this is the sum total of my experience in Akiachak. Intermittent rain storms and the aforementioned fact that it was Sunday (and everything was closed) kept us from interacting with anyone from the town or getting a real sense of its vibe. So far, every town has its own unique personality, but with Akiachak I did not experience any of this. It is the curse of this job, really; we blow into town long enough only to get the barest feel of a place, and then, like a puff of smoke or a light breeze, are gone.

A brief note on puddle jumping...

We have touched down in some fairly obscure villages, popping in to drop off mail, passengers, a hot water heater, or whatever else made its way onto the plane that happened to be flying our route. The scenery is no less than majestic, if a bit hard to explain. This section of the state is mostly flat, dotted with small ponds and larger lakes, with circles of algae or land blooming seemingly out of nothing.

On our way out of Newtok we passed over a herd of muskox, our pilot flying low to afford us a view of the animals. The flight involved a lot of sharp banks, giving us an outstanding view of gently sloping hillsides and the potential for archaeological sites (according to my companion; I, of course, am no expert on that). It also is the only time I felt that I might toss my cookies. The small plane flights have been remarkably smooth and easy, assuming a high ride over still terrain. It's only when the turns are tight and the items on the ground are moving that my stomach has coiled in on itself, making the flight out of Newtok on of the most beautiful and simultaneously dizzying.

When we stopped to drop off a passenger, I jumped out for a brief feel of still ground and a few deep breaths of fresh, cooling air. Another difference between small plane flights and those of commercial jets are the relative freedoms: freedom to open your own door, freedom to allow yourself a few brief if necessary moment out of the plane. The "ground crew" --- a couple of local guys on 4-wheelers --- seemed amused at my novice status, but were kind and welcoming for the 3 minutes I was on their land.

And the last perk of small plane flight: the ability of yours truly to pass out in mere minutes once off the ground. It feels so much like being in the passenger seat of a car that I can't help but close my eyes and feel at peace, riding high above this beautiful land.

Monday, July 16, 2012

Kwigillionok

Day Three: Saturday, July 14, 2012, Kwigillionok, or Kwig for short. We were met at the airport by our tribal village contact, Emma, a wonderful soft-spoken lady with a 4WD vehicle. She provided us with transportation from the airport to the opposite side of town, expertly steering her vehicle along the boardwalks, not even slowing when other 4-wheelers sped past on the narrow wooden paths. In Kwig, the boardwalks are in much better condition than those we saw in Newtok; this town is not threatened, and appears to be thriving in a combination of traditional and modern ways.

Our fieldwork finished, Emma returned to give us a lift to the village store, which doubles as a workshop for a family of traditional kayak builders. Bill, the patriarch of the family, was kind enough to show us around. The tour included a look at his father-in-law's hand-built model, a boat Bill constructed for his son, and one that was built from a grant by the National Park Service and is a museum-quality example of a traditional Inuit boat. The ribs are constructed of drift wood, collected along the water's shores from forests a hundred miles away, and hand formed with knives and teeth. The skin of the boat is seal skin, lashed with seal skin cured in urine and and caulked with a paste made of moss. Everything is done by hand with local materials, down to the paint, made of a paste from local blue or red stones. Bill also showed us paddles, harpoons, and hand-made knives, all of which I would have loved to buy, none of which could I afford. Instead, we purchased the book his father-in-law wrote, which details how to build a traditional kayak and has wonderful pictures of the family building the boat.

Our fieldwork finished, Emma returned to give us a lift to the village store, which doubles as a workshop for a family of traditional kayak builders. Bill, the patriarch of the family, was kind enough to show us around. The tour included a look at his father-in-law's hand-built model, a boat Bill constructed for his son, and one that was built from a grant by the National Park Service and is a museum-quality example of a traditional Inuit boat. The ribs are constructed of drift wood, collected along the water's shores from forests a hundred miles away, and hand formed with knives and teeth. The skin of the boat is seal skin, lashed with seal skin cured in urine and and caulked with a paste made of moss. Everything is done by hand with local materials, down to the paint, made of a paste from local blue or red stones. Bill also showed us paddles, harpoons, and hand-made knives, all of which I would have loved to buy, none of which could I afford. Instead, we purchased the book his father-in-law wrote, which details how to build a traditional kayak and has wonderful pictures of the family building the boat.

Bethel

Bethel is our hub for the week, about 350 miles west of Anchorage on the Kuskokwim River. This town is organized, especially when it comes to the cabs and flights (which, granted, is about all we are being exposed to). We have never waited more than 2 minutes for a taxi, and our flights into and out of the Era, Bering, and Alaska terminals have been on time every time. There is a minor issue of "weather permitting," but more on that later.

The Longhouse is where we are staying, nothing fancy but clean, the only issue the paper thin walls and the doors that slam horrifically loud no matter how gently you try to close them. The Red Blanket restaurant is attached to the hotel, and Moon, the waitress, has taken excellent care of us for multiple American-style meals. We ventured out to Dimitri's as well, a Greek-owned restaurant with an Italian bent and the typical burger fare found everywhere else up here. It came highly recommended, and was quite yum - I stayed away from the burgers and went for a salad with a delicious and light homemade vinaigrette dressing, and cheese ravioli.

The local grocery is horrifically expensive for some coming from the lower 48, but has everything you could hope for. My biggest complaint is the complete lack of seafood when I am surrounded by water. Lindsay noted that it is worth more to export, so it's hard to find here. Makes me realize that there are some things horribly wrong with the way the world runs these days.

The Longhouse is where we are staying, nothing fancy but clean, the only issue the paper thin walls and the doors that slam horrifically loud no matter how gently you try to close them. The Red Blanket restaurant is attached to the hotel, and Moon, the waitress, has taken excellent care of us for multiple American-style meals. We ventured out to Dimitri's as well, a Greek-owned restaurant with an Italian bent and the typical burger fare found everywhere else up here. It came highly recommended, and was quite yum - I stayed away from the burgers and went for a salad with a delicious and light homemade vinaigrette dressing, and cheese ravioli.

The local grocery is horrifically expensive for some coming from the lower 48, but has everything you could hope for. My biggest complaint is the complete lack of seafood when I am surrounded by water. Lindsay noted that it is worth more to export, so it's hard to find here. Makes me realize that there are some things horribly wrong with the way the world runs these days.

Sunday, July 15, 2012

Newtok

Day two found us in Newtok on Friday, July 13, 2012. We began our day with a 6am flight from Anchorage to Bethel, where we had enough time to check in to our hotel rooms at the Longhouse. Back to the airport and off to Newtok, located on the edge of Ninglick River. The river has been slowly encroaching and the entire village is under threat. Built on permafrost, which is melting under rising temperatures, most buildings list dangerously on unstable foundations.

Upon arrival we were met by George, the Era agent, who transported us on the back of his 4-wheeler from the airport into town. The ride was an adventure, with Lindsay and I holding on to the back, our arms wrapped tightly around a large cardboard box that was also unloaded from the airplane. The "roads" are boardwalks, elevated wooden structures above the marshy and unstable land, and they are in need of repair. Knowing that the village will soon be abandoned to the mercy of the river, little if any maintenance is being performed on the infrastructure.

As we worked to document the buildings, we were quickly swarmed by the village children. The adorable tykes came on bikes and via foot, ranging in ages and all exceedingly friendly. They ended up showing us around the village en masse, including a brief but ill-fated jaunt on a 4WD we rented from the Tribal Center. At first they followed along shouting locations of friends and family, until our ride turned up with a flat tire. We returned our short-term rental, and proceeded for the rest of the day on foot --- arguably the safer route given the relative condition of the boardwalks.

After a while we headed to George's to warm up with a cup of coffee and a chat with him and his wife. He told us how, when he was young, the river was several miles away from his house. Today, his property is riverfront, the rushing waters perhaps a quarter-mile away at the most. He and his family will likely relocate when the town does, leaving behind miles of vacated boardwalks and the wood post remnants of fish drying racks.

Point Hope

Day one of fieldwork was in Point Hope on Thursday, July 12, 2012. An early morning flight from Anchorage to Kotzebue was fairly typical, then about an hour hop to Point Hope. The sun was shining, and there wasn't a cloud in the sky --- as our pilot said, it doesn't get any more perfect than this.

Upon arrival in Point Hope we were greeted by a small group of people in trucks and on ATVs, eager to collect the cargo that outweighed us on the flight. Everything that comes into these small communities must arrive by flight, which can be exceptionally expensive, or via boat, the slower if more cost efficient route.

Point Hope is one of the western-most points in the U.S., though it moved a bit to the east in the 1970s. Located on a gravel bar that protrudes into the Chukchi Sea, continual erosion forced the relocation of the entire town. The new location is characterized by modern and rather unappealing government housing, but vestiges of the old town still remain west of the airport. The traditional, semi-subterranean housing (often made with whale bone "studs") seems like it would be much more comfortable for the -50 degree Fahrenheit winters that are common in this part of the world.

Aside from the fieldwork, we had an opportunity to eat at the local restaurant, the Whaler's Inn, operated by a wonderfully friendly guy named John. The community is also home to some artisan craftspeople who practice traditional carving and jewelry making. Visitor's are obviously a relative rarity, as no fewer than half a dozen villagers approached us with baleen plaques, fossilized ivory earrings, hand carved walrus tusks and ram's horns. We also spoke with a traditional mask maker whose work has been featured in art museums all over Alaska and in the Lower 48. In general, the village was extremely welcoming, and made us feel very much at home for the brief period we were there.

By 4pm, about the time we were headed back down to the airport, we looked to the south and noticed a fog bank rolling in. I had been warned that the weather can be at best unpredictable, but the expediency with which the entire town was blanketed was amazing. By the time we reached the airport the town - both old and new - had completely vanished into the mist. Our plane barely made the landing through the fog, though the take off was remarkably smooth. Just a few feet above the earth we broke through and were able to see the thick white blanket below us, and the beautiful blue of the sky everywhere else. Back to Kotzebue, a hop to Nome, and we arrived back in Anchorage exhausted and looking forward to doing it all again in less that 6 hours.

Friday, July 13, 2012

"...off in a storm of whale shit"

Apparently, it's an old family saying. Lindsay, my travel companion on this adventure, shared this clan colloquialism just as the pilot began taxing for my first-ever bush flight. Something her father used to say before a road trip, she commented that since moving to Alaska the phrase has become even more appropriate for her life.

Lindsay and I will spend the next 8 or so days together flying in and out of some fairly remote tribal villages. As always, my role will be to conduct architectural survey, though these particular buildings are nothing to blog about. The real story for this scope of work is in the communities. These small villages are some of the last remaining vestiges of traditional Eskimo lifeways, and mark a unique culture that I am only limitedly familiar with.

Our trip includes 16 flights in 7 days, not including my own flights into and out of Anchorage. Most of these are on small, single- or dual-prop planes, taking off and landing on runways of gravel. So far, we have visited two of six villages on our docket. The schedule of flights and surveys has been grueling, with barely 4 hours of sleep each night since I arrived in Alaska 3 days ago. Tomorrow, I will share thoughts on Point Hope, Newtok, and our current hub of Bethel. Tonight, I have 10 free hours between flights, and 9 of those I intend to spend with my eyes closed.

Lindsay and I will spend the next 8 or so days together flying in and out of some fairly remote tribal villages. As always, my role will be to conduct architectural survey, though these particular buildings are nothing to blog about. The real story for this scope of work is in the communities. These small villages are some of the last remaining vestiges of traditional Eskimo lifeways, and mark a unique culture that I am only limitedly familiar with.

Our trip includes 16 flights in 7 days, not including my own flights into and out of Anchorage. Most of these are on small, single- or dual-prop planes, taking off and landing on runways of gravel. So far, we have visited two of six villages on our docket. The schedule of flights and surveys has been grueling, with barely 4 hours of sleep each night since I arrived in Alaska 3 days ago. Tomorrow, I will share thoughts on Point Hope, Newtok, and our current hub of Bethel. Tonight, I have 10 free hours between flights, and 9 of those I intend to spend with my eyes closed.

Lindsay and our pilot, Aaron, on our way to Point Hope. We were definitely NOT the most precious cargo: those are boxes of frozen White Castle hamburgers, presumably on their way to the Village store.

Me, on my first ever bush flight (and first small aircraft flight?).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)